At Lincoln, Marshall counted among his classmates the great poet and writer Langston Hughes; he pledged Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, as did my grandfather, Marcus Carpenter — and yes, this network helped me connect with the justice. He often used the nickname “knucklehead” for his law clerks. He called me “gal,” as in, “When are you going to get married, gal?” I related to him much the way I would with my grandfather, his fraternity brother. In his cavernous personal office, surrounded by mementos of his iconic life, I would often talk and laugh with the man we clerks called “Boss.” He enthralled me with stories, of hysterical fraternity pranks, of hanging out with Hughes in Harlem with a hip literary crowd, of narrowly escaping mob vengeance as Mr. Civil Rights. I could see how he had enraptured courtrooms as a legal advocate.

After Marshall endured indignities at a segregated movie theater, Hughes confronted him and persuaded him to see Negro faculty as a positive with a rightful place in their education. His social conscience was piqued even more when he entered Howard Law School where Dean Charles Hamilton Houston — a Harvard Law School grad later dubbed “the man who killed Jim Crow” — remade the school as an engine of social change.

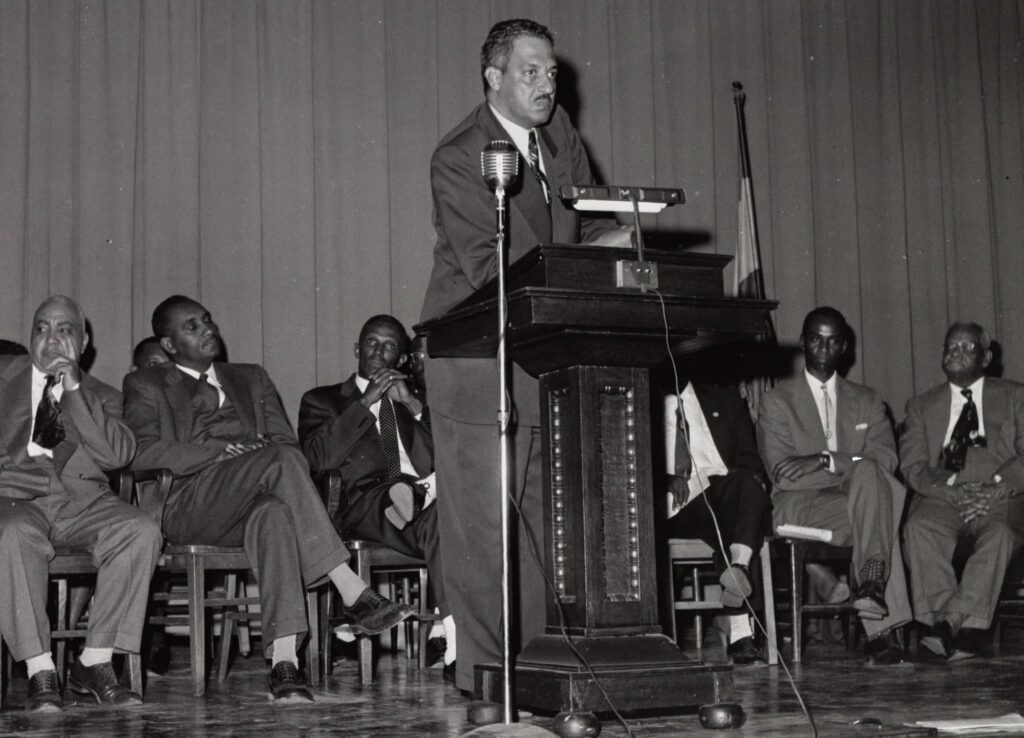

Marshall graduated first in his class and began working with Houston, his mentor. Together they sued the University of Maryland law school that had refused to admit Marshall five years earlier because he was Black; they won admission for Donald Murray in 1936, the first of several victories knocking out planks of Jim Crow. Marshall would eventually succeed Houston as general counsel for the NAACP and remake the civil rights law firm they invented as the Legal Defense Fund. In his two decades as head of LDF and later as Solicitor General of the United States, he argued 32 cases before the Supreme Court and won 29 of them — an unparalleled record that President Lyndon Johnson touted when he nominated him to the Court in 1967.

That’s when Marshall himself became an integration pioneer, the first non-white justice ever to serve on the court, confirmed by the U.S. Senate in a 69-11 majority. Most of the senators who voted against his nomination were segregationists like Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-S.C.).

Growing up in the ‘60s and ‘70s, I’d long admired Marshall, someone my family, civil rights activists themselves, held up as a quintessential “race man,” who expanded our freedoms (and that of others). But it took Randall Kennedy, my professor at Harvard Law School who’d also clerked for Marshall, to persuade me to apply. My grandmother urged me — repeatedly — to mention that I was Marcus Carpenter’s granddaughter. I did as I was told, adding a handwritten note to that effect at the bottom of my cover letter.

I am sure that connection and Kennedy’s recommendation helped. As an honor student, member of the Harvard Law Review with law degrees from Oxford University and Harvard, I certainly was qualified, but none of the other justices I applied to interviewed me.

Upon starting the job, I wasn’t nervous — a previous clerkship boosted my confidence in my clerking bona fides — but I was cautious. I was not sure how to relate to him. Did he even know my name?

But the first week I got some reassurance: William Brennan Jr. retired and Marshall called me on the phone and asked me to write his press statement on Brennan’s retirement. He began with his husky voice, “Sheryll …” and told me the news and what he wanted to say. I was shocked that Brennan had retired and surprised that Boss wanted me to draft a statement for him. From then on, I knew that, as the only woman among his clerks and only the second Black woman he had as a clerk, I was in a special position with him. I was the only girl in my family and the youngest among my siblings and I was used to special attention from my father. For the rest of the year, working under Boss, it felt a bit like that. I remember, fondly, a clerk’s reunion, where he pointed me out to an attendee.

“This is my special,” he said.

I wanted to make him proud.

In preparing for Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, I read every school case decided by the Supreme Court and he remembered all of them. He explained to me his view that a desegregation decree should not be lifted so long as there were feasible methods for avoiding the racially identifiable schools that stigmatized Black children as inferior, according to the Brown Court. At one weekly meeting, he asked how I was coming with his draft dissent, and I begged for a month to complete it.

“I love you gal,” he said with a smile, “but you got a week.”

Above all what I learned from Marshall during my year of clerking for him and in decades of reading and teaching his opinions, mainly dissents, is that the Black American quest for equality has been central to fulfilling the founding ideals of this country. Each generation has to keep fighting to make those values real in the lives of all people.

Sheryll Cashin writes about race relations and inequality in America. Her new book White Space, Black Hood: Opportunity Hoarding and Segregation in the Age of Inequality (September 2021) shows how government created “ghettos” and affluent white space and entrenched a system of American residential caste that is the linchpin of US inequality—and issues a call for abolition. Her book Loving: Interracial Intimacy in America and the Threat to White Supremacy explores the history and future of interracial intimacy, how white supremacy was constructed and how “culturally dexterous” allies may yet kill it. Her book Place Not Race was nominated for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Non-Fiction in 2015. Her book The Failures of Integration was an Editors’ Choice in the New York Times Book Review. Cashin is also a three-time nominee for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for non-fiction (2005, 2009, and 2018). She has written commentaries for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Salon, The Root, and other media and is currently a contributing editor for Politico Magazine.

Cashin is Professor of Law at Georgetown University where she teaches Constitutional Law, and Race and American Law among other subjects. She is an active member of the Poverty and Race Research Action Council and worked in the Clinton White House as an advisor on urban and economic policy, particularly concerning community development in inner-city neighborhoods. She was law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Cashin was born and raised in Huntsville, Alabama, where her parents were political activists. She currently resides in Washington, D.C., with her husband and two sons.